|

| HISTORY |

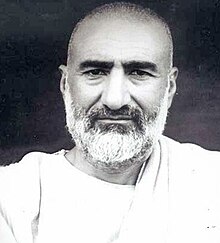

| Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan | |

|---|---|

Khan pictured in the 1940s | |

| Born | c. 1890 Hashtnagar, Utmanzai,Charsadda, North-West Frontier Province, British India |

| Died | 1988 Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan |

| Resting place | Jalalabad, Afghanistan |

| Other names | Badshah Khan, Bacha Khan, Sarhaddi Gandhi, Fakhr-e-Afghan |

| Organization | Khudai Khidmatgar, Indian National Congress, National Awami Party |

| Political movement | Indian Independence Movement |

| Religion | Islam |

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1890 - 20 January 1988) (Pashto: خان عبدالغفار خان) was an Afghan, Pashtun political and spiritual leader known for his non-violent opposition to British Rule in India. A lifelong pacifist, a devout Muslim,[1] and a close friend of Mohandas Gandhi, he was also known as Fakhri Afghan ("The Afghan pride"), Badshah Khan (alsoBacha Khan, Pashto: lit., "King Khan") and Sarhaddi Gandhi (Urdu, Hindi lit., "Frontier Gandhi").

His family encouraged him to join the British Indian Army, but a British Raj officer's mistreatment of a countryman offended him. A family decision for him to study in England was put off after his mother's intervention.

Having witnessed the repeated failure of revolts against the British Raj, he decided social activism and reform would be more beneficial for Pashtuns. This ultimately led to the formation of the Khudai Khidmatgar movement (Servants of God). The movement's success triggered a harsh crackdown against him and his supporters and he was sent into exile. It was at this stage in the late 1920s that he formed an alliance with Gandhi and the Indian National Congress. This alliance was to last till the 1947 partition of India.

Ghaffar Khan strongly opposed the Muslim League's demand for the partition of India.[2][3]When the Indian National Congress accepted the partition plan, he told them "You have thrown us to the wolves."[4]

After partition, Ghaffar Khan was frequently arrested by the Pakistani government in part because of his association with India and his opposition to authoritarian moves by the government. He spent much of the 1960s and 1970s either in jail or in exile.

In 1985 he was nominated for the Nobel peace prize. In 1987 he became the first person without Indian citizenship to be awarded the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award. Upon his death in 1988, following his wishes, he was buried in Jalalabad. Despite the heavy fighting at the time, both sides in the Afghan war declared a ceasefire to allow his burial.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Early years

Ghaffar Khan was born into a generally peaceful and prosperous family from Utmanzai in the Peshawar Valley of British India. His father, Behram Khan, was a land owner in the area commonly referred to as Hashtnaggar. Ghaffar was the second son of Behram to attend the British run Edward's mission school since this was the only fully functioning school because it was run by missionaries. At school the young Ghaffar did well in his studies and was inspired by his mentor Reverend Wigram to see the importance of education in service to the community. In his 10th and final year of high school he was offered a highly prestigious commission in The Guides, an elite corp of Pashtun soldiers of the British Raj. Young Ghaffar refused the commission after realising even Guide officers were still second-class citizens in their own country. He resumed his intention of University study and Reverend Wigram offered him the opportunity to follow his brother, Dr. Khan Sahib, to study in London. An alumnus of Aligarh Muslim University,he eventually received the permission of his father, Ghaffar's mother wasn't willing to lose another son to London—and their own culture and religion. So Ghaffar began working on his father's lands while attempting to discern what more he might do with his life. [5]

[edit]Ghaffar "Badshah" Khan

In response to his inability to continue his own education, Ghaffar Khan turned to helping others start theirs. Like many such regions of the world, the strategic importance of the newly formed North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan) as a buffer for the British Raj from Russian influence was of little benefit to its residents. The oppression of the British, the repression of the mullahs, and an ancient culture of violence and vendetta prompted Ghaffar to want to serve and uplift his fellow men and women by means of education. At 20 years of age, Ghaffar opened his first school in Utmanzai. It was an instant success and he was soon invited into a larger circle of progressively minded reformers.

While he faced much opposition and personal difficulties, Ghaffar Khan worked tirelessly to organize and raise the consciousness of his fellow Pushtuns. Between 1915 and 1918 he visited 500 villages in all part of the settled districts of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. It was in this frenzied activity that he had come to be known as Badshah (Bacha) Khan (King of Chiefs).[5]

He married his first wife Meharqanda in 1912; she was a daughter of Yar Mohammad Khan of the Kinankhel clan of the Mohammadzai tribe of Razzar, a village adjacent to Utmanzai. They had a son in 1913, Abdul Ghani Khan, who would become a noted artist and poet. Subsequently, they had another son, Abdul Wali Khan (17 January 1917–), and daughter, Sardaro. Meharqanda died during the 1918 influenza epidemic. In 1920, Abdul Ghaffar Khan remarried; his new wife, Nambata, was a cousin of his first wife and the daughter of Sultan Mohammad Khan of Razzar. She bore him a daughter, Mehar Taj (25 May 1921–), and a son, Abdul Ali Khan (20 August 1922-19 February 1997). Tragically, in 1926 Nambata died early as well from a fall down the stairs of the apartment they were staying at in Jerusalem.[6]

[edit]Khudai Khidmatgar

In time, Ghaffar Khan's goal came to be the formulation of a united, independent, secular India. To achieve this end, he founded the Khudai Khidmatgar ("Servants of God"), commonly known as the "Red Shirts" (Surkh Posh), during the 1920s.

The Khudai Khidmatgar was founded on a belief in the power of Gandhi's notion of Satyagraha, a form of active non-violence as captured in an oath. He told its members:

"I am going to give you such a weapon that the police and the army will not be able to stand against it. It is the weapon of the Prophet, but you are not aware of it. That weapon is patience and righteousness. No power on earth can stand against it."[7]

The organization recruited over 100,000 members and became legendary in opposing (and dying at the hands of) the British-controlled police and army. Through strikes, political organisation and non-violent opposition, the Khudai Khidmatgar were able to achieve some success and came to dominate the politics of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. His brother, Dr. Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan (known as Dr. Khan Sahib), led the political wing of the movement, and was the Chief Minister of the province (from the late 1920s until 1947 when his government was dismissed byMohammad Ali Jinnah of the Muslim League).

[edit]Ghaffar Khan & the Indian National Congress

Main article: Indian National Congress

Ghaffar Khan forged a close, spiritual, and uninhibited friendship with Mahatma Gandhi, the pioneer of non-violent mass civil disobedience in India. The two had a deep admiration towards each other and worked together closely till 1947.[2][3]

The Khudai Khidmatgar (servants of god) agitated and worked cohesively with the Indian National Congress, the leading national organization fighting for freedom, of which Ghaffar Khan was a senior and respected member. On several occasions when the Congress seemed to disagree with Gandhi on policy, Ghaffar Khan remained his staunchest ally. In 1931 the Congress offered him the presidency of the party, but he refused saying, "I am a simple soldier and Khudai Khidmatgar, and I only want to serve."[8] He remained a member of the Congress Working Committee for many years, resigning only in 1939 because of his differences with the Party's War Policy. He rejoined the Congress Party when the War Policy was revised.

On April 23, 1930, Ghaffar Khan was arrested during protests arising out of the Salt Satyagraha. A crowd of Khudai Khidmatgar gathered in Peshawar's Kissa Khwani (Storytellers) Bazaar. The British ordered troops to open fire with machine guns on the unarmed crowd, killing an estimated 200-250.[9] The Khudai Khidmatgar members acted in accord with their training in non-violence under Ghaffar Khan, facing bullets as the troops fired on them.[10] Two platoons of the The Garhwal Rifles regiment refused to fire on the non-violent crowd. They were later court-martialled with heavy punishment, including life imprisonment.

Ghaffar Khan was a champion of women's rights and nonviolence. He became a hero in a society dominated by violence; notwithstanding his liberal views, his unswerving faith and obvious bravery led to immense respect. Throughout his life, he never lost faith in his non-violent methods or in the compatibility of Islam and nonviolence. He viewed his struggle as a jihad with only the enemy holding swords. He was closely identified with Gandhi because of his non-violence principles and he is known in India as the 'Frontier Gandhi'.[3] One of his Congress associates was Pandit Amir Chand Bombwal of Peshawar.

"O Pathans! Your house has fallen into ruin. Arise and rebuild it, and remember to what race you belong." -- Ghaffar Khan[11]

[edit]The Partition

Main article: Partition of India

See also: Babrra massacre

Ghaffar Khan strongly opposed the partition of India.[2][3] While many Pashtuns (particularly the Red Shirts) were willing to work with Indian politicians, many other Pashtuns were sympathetic to the idea of a separate homeland for India's Muslims following the departure of the British. Targeted with being Anti-Muslim, Ghaffar Khan was attacked in 1946, leading to his hospitalization in Peshawar.[12]

The Congress party refused last-ditch compromises to prevent the partition, like the Cabinet Mission plan and Gandhi's suggestion to offer the Prime Ministership to Jinnah. As a result Badshah Khan and his followers felt a sense of betrayal by both Pakistan and India. Badshah Khan's last words to Gandhi and his erstwhile allies in the Congress party were: "You have thrown us to the wolves."[4]

When the referendum over accession to Pakistan was held, Badshah Khan and the Indian National Congress Party boycotted the referendum. As a result, in 1947 the accession ofKhyber-Pakhtunkhwa to Pakistan was made possible by a slight majority of the 50.1% votes cast. A loya jirga in the Tribal Areas also garnered a similar result as most preferred to become part of Pakistan. Ghaffar Khan and his Khudai Khidmatgars, however, chose to boycott the polls along with other nationalistic Pakhtuns. Some have argued that a segment of the population voted was barred from voting,.[13]

[edit]Arrest and exile

Main article: Pakistan Movement

See also: National Awami Party and One Unit

Ghaffar Khan took the oath of allegiance to the new nation of Pakistan on 23 February 1948 at the first session of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly.[14]

He pledged full support to the government and attempted to reconcile with the founder of the new state Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Initial overtures led to a successful meeting in Karachi, however a follow-up meeting in the Khudai Khidmatgar headquarters never materialised, allegedly due to the role of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Chief Minister, Abdul Qayyum Khan who warned Jinnah that Ghaffar Khan was plotting his assassination.[15][16]

Following this, Ghaffar Khan formed Pakistan's first National opposition party, on 8 May 1948, the Pakistan Azad Party. The party pledged to play the role of constructive opposition and would be non-communal in its philosophy.

However, suspicions of his allegiance persisted and under the new Pakistani government, Ghaffar Khan was placed under house arrest without charge from 1948 till 1954. Released from prison, he gave a speech again on the floor of the constituent assembly, this time condemning the massacre of his supporters at Babrra.[17]

"I had to go to prison many a time in the days of the Britishers. Although we were at loggerheads with them, yet their treatment was to some extent tolerant and polite. But the treatment which was meted out to me in this Islamic state of ours was such that I would not even like to mention it to you."[18]

He was arrested several times between late 1948 and in 1956 for his opposition to the One Unitscheme.[19] The government attempted in 1958 to reconcile with him and offered him a Ministry in the government, after the assassination of his brother, he however refused.[20] He remained in prison till 1957 only to be re-arrested in 1958 until an illness in 1964 allowed for his release.[21]

In 1962, Abdul Ghaffar Khan was named an "Amnesty International Prisoner of the Year". Amnesty's statement about him said, "His example symbolizes the suffering of upward of a million people all over the world who are prisoners of conscience."

In September 1964, the Pakistani authorities allowed him to go to United Kingdom for treatment. During winter his doctor advised him to go to United States. He then went into exile to Afghanistan, he returned from exile in December 1972 to a popular response, following the establishment of National Awami Party provincial government in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa andBalochistan.

He was arrested by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's government at Multan in November 1973 and described Bhuttos government as "the worst kind of dictatorship".[22]

In 1984, increasingly withdrawing from politics he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.[23]He visited India and participated in the centennial celebrations of the Indian National Congress in 1985; he was awarded the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding in 1967[24] and later Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award, in 1987.[25]

His final major political challenge was against the Kalabagh dam project, fearing that the project would damage the Peshawar valley, his hostility to it would eventually lead to the project being shelved after his death.

Ghaffar Khan died in Peshawar under house arrest in 1988 and was buried in Jalalabad, Afghanistan according to his wishes. This was a symbolic move by Ghafar Khan, this would allow his dream of Pakhtun unification to live even after his death. The then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi had gone to Peshawar, to pay his tributes to Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in spite of the fact that General Zia-ul-Haq had tried to stall his attendance citing security reasons, also the Indian government declared a five-day period of mourning in his honour.[25]

Although he had been repeatedly imprisoned and persecuted, tens of thousands of mourners attended his funeral, described by one commentator as a caravan of peace, carrying a message of love from Pashtuns east of the Khyber to those on the west,[15] marching through the historic Khyber Pass from Peshawar to Jalalabad. A cease-fire was announced in the Afghan Civil War to allow the funeral to take place, even though it was marred by bomb explosions killing 15.[26]

[edit]Political legacy

His eldest son Ghani Khan was a poet, his other son Khan Abdul Wali Khan is the founder and leader of the Awami National Party and was the Leader of the Opposition in the Pakistan National Assembly. Ghaffar Khans family was the frequent target of government arrests due to their involvement in politics and being accused of being anti-Pakistani.

His third son Khan Abdul Ali Khan was non-political and a distinguished educator, and served as Vice-Chancellor of University of Peshawar. Ali Khan was also the head ofAitchison College, Lahore and Fazle Haq college, Mardan.

Mohammed Yahya Education Minister of N W F Province, was the only son in law of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan.

Asfandyar Wali Khan is the grandson of Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, and leader of the Awami National Party, the party in power in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

Salma Ataullahjan is the great grand niece of Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan and a member of the Senate of Canada.

|

| HISTORY OF KHAN ABDUL GHAFFAR KHAN |

No comments:

Post a Comment